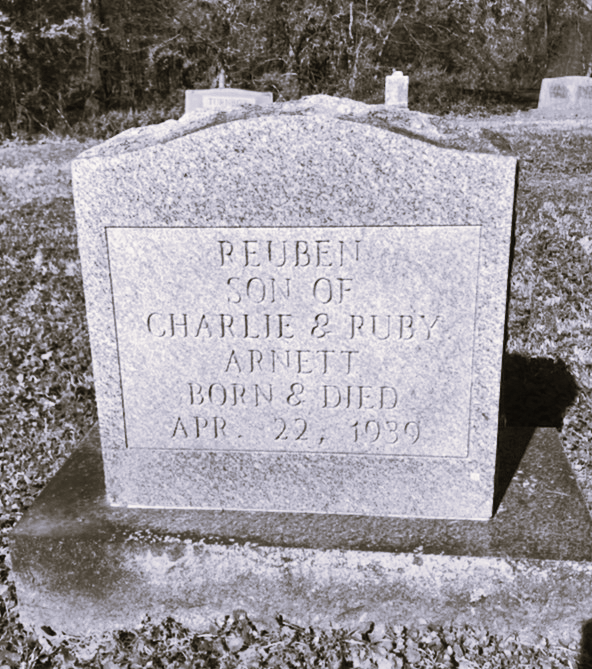

Eighty-six years ago today, my oldest brother was born. And died.

He lived only a few hours, held but briefly. Mom and Dad’s firstborn passed without knowing any of this world’s joys or heartaches, never knew any of his six younger sisters and brothers. He was mourned only by our parents and a very few of their closest friends in Henderson, Tennessee, where Dad was attending Freed-Hardeman College in the preacher training program. The day after his birth and death, he was buried in Antioch Cemetery near Browns Grove, Kentucky, a hundred miles away, the area where generations of Arnett’s had lived and died. And some still live.

For nearly fifty years, he lay beneath the sod, un-named and barely mentioned. Only a small metal marker gave any indication of his place in the soil behind the church: “Arnett, Infant Son.”

Mom and Dad rarely spoke of him in the days of my growing up; I had only a vague notion, little more than a slight awareness. Dad’s own father had died just two weeks before he was born and Dad himself was a sickly baby.

“They called me a ‘blue baby,’” he related, “They weren’t sure if I was going to live or not.” The condition arises from a lack of circulation, often caused by some type of heart deformity but sometimes due to other causes, possibly including contaminated well water. Since he lived almost ninety-six years, it would appear that any heart issue was resolved without human intervention.

Mom’s doctor reportedly decided any human intervention was pointless for her own first child. He made no effort to save the baby’s life.

Dad preached at Antioch the next morning and made no mention of their loss. Not wanting to inconvenience others nor advertise his own loss, he and two friends waited until everyone else had left after the morning service and then buried the baby. A small hole, one brief prayer, a single tiny mound of light brown soil turned to light amidst spring’s fresh green.

And so, there he lay for nearly half a century, un-named and mostly un-mentioned.

Until a late night conversation in the mid-Eighties at the dining table in Mom and Dad’s log house near Coldwater, Kentucky. For nearly two hours after Dad had gone to bed, Mom and I sat at the dining table, talking in low voices. I was home for a brief visit from grad school in Ohio.

We’d spent the afternoon re-visiting some of the places where she and Dad had lived and had visited the Antioch cemetery where they had already placed the stone to mark their own future resting sites. Names and dates of birth already engraved; the other dates left blank. And still, next to their stone, that tiny metal marker.

“Did you have a name picked out?” I asked her there in the kitchen light of that night’s talking. “If you will pick out a name, I’ll see to it that he gets a marker.”

She paused only for a moment. “I always liked the name ‘Reuben,’” she answered quietly while a look of tender pain played in her eyes and brushed softly between stray strands of gray hair that played across the edges of her face.

“Reuben.” Firstborn of the sons of Jacob. Eldest brother. The one who knew when jealousy had gone too far and intervened to keep alive the despised baby brother. Having no idea that that twisted mercy would one day save all their lives. Without much thought to the grief they would bring to their own father.

It is hard to exaggerate the delightful expectancy of a loving couple’s deeply desired firstborn. Hard to overstate the pain and disappointment the death of one so anticipated, so longed for and loved even though unseen. The long, aching pain to feel the change of excitement and celebration twisting into grief and heartache. So hard then to bless the name of the God who gives and takes away.

Fifty years is a long time to trace life with so little acknowledgement of such deep hurt.

There was no further mention of the conversation between us.

But the next time I visited Antioch Cemetery, there was a brand new marker there. A name and date chiseled in marble, finally marking their grief, finally honoring the baby they’d lost, acknowledging their wounding, and declaring to passersby that even this child—who breathed only briefly the air of this world’s painful and precarious nature—deserved a name. That he had parents, and that though he lived only briefly, he, too, held a place in their lives.

And, although perhaps in ways so small as to be barely mentioned or measured, a place, too, in the lives of his sisters and brothers who never knew him. And yet, grew up in his shadow.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Walker Arnett, my thirdborn son, who lives in West Kentucky. Eight generations… and counting.